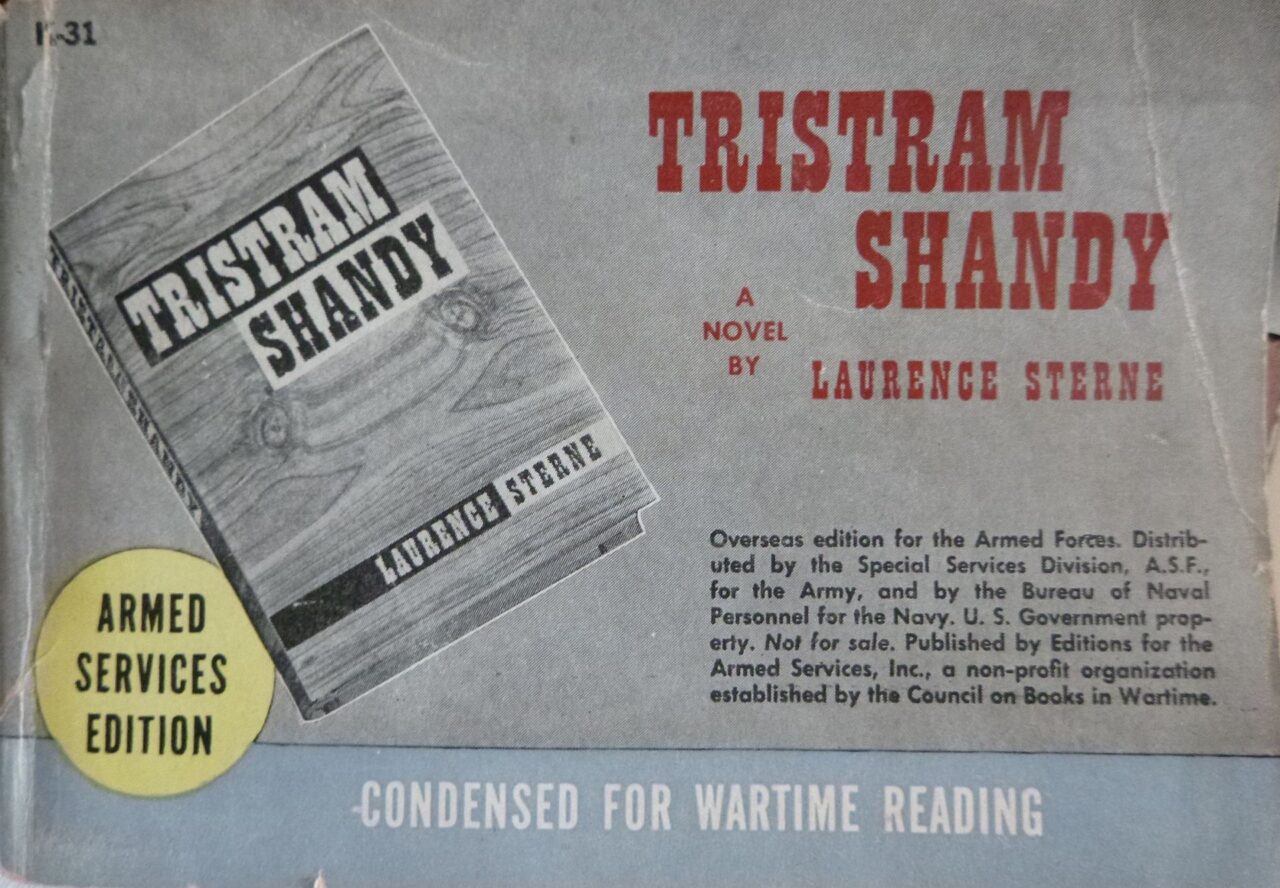

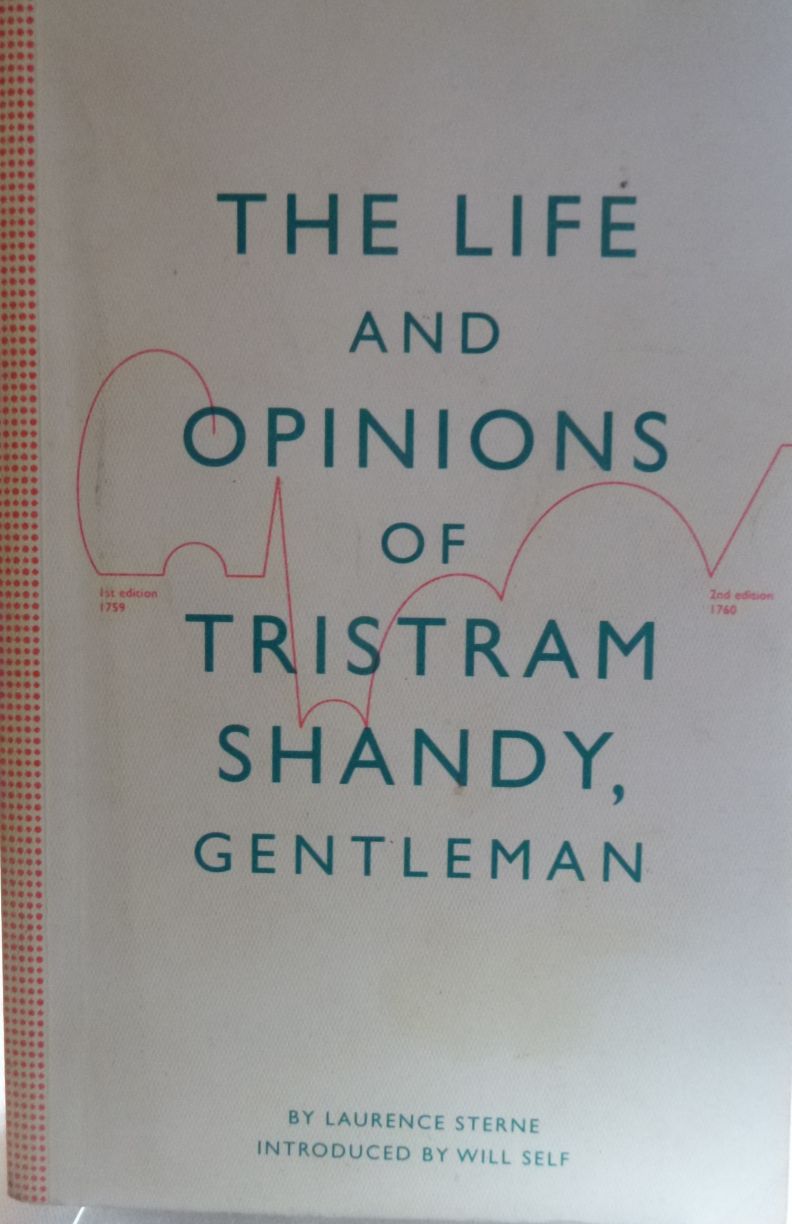

The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman

When The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman was launched upon an unsuspecting world it excited everyone in one way or another. It scandalised some with its bawdy humour, filled others with delight, and baffled many others. One of the first reviewers in 1760 was almost lost for words, describing it as ‘a humorous performance, of which we are unable to convey any distinct ideas to our readers’.

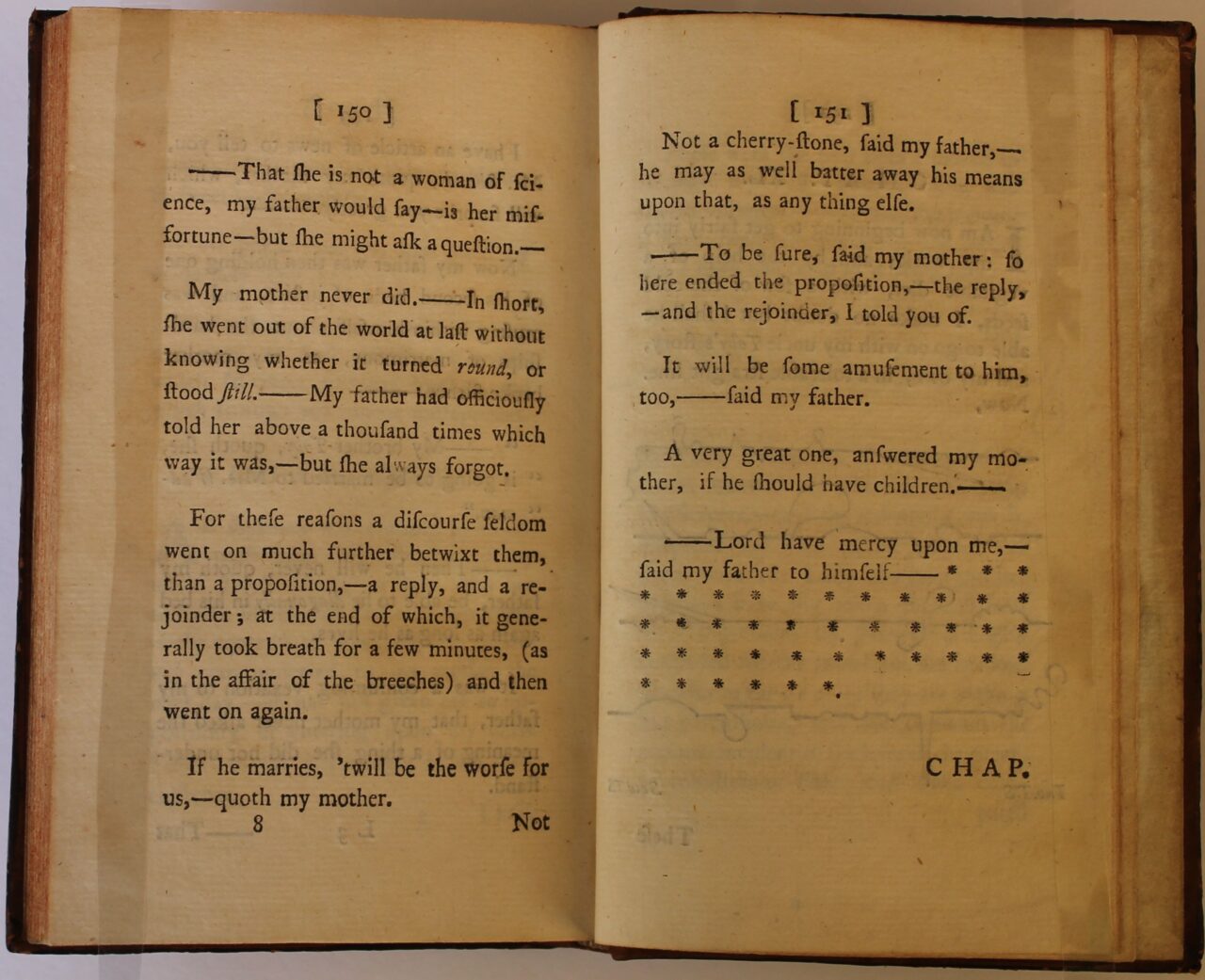

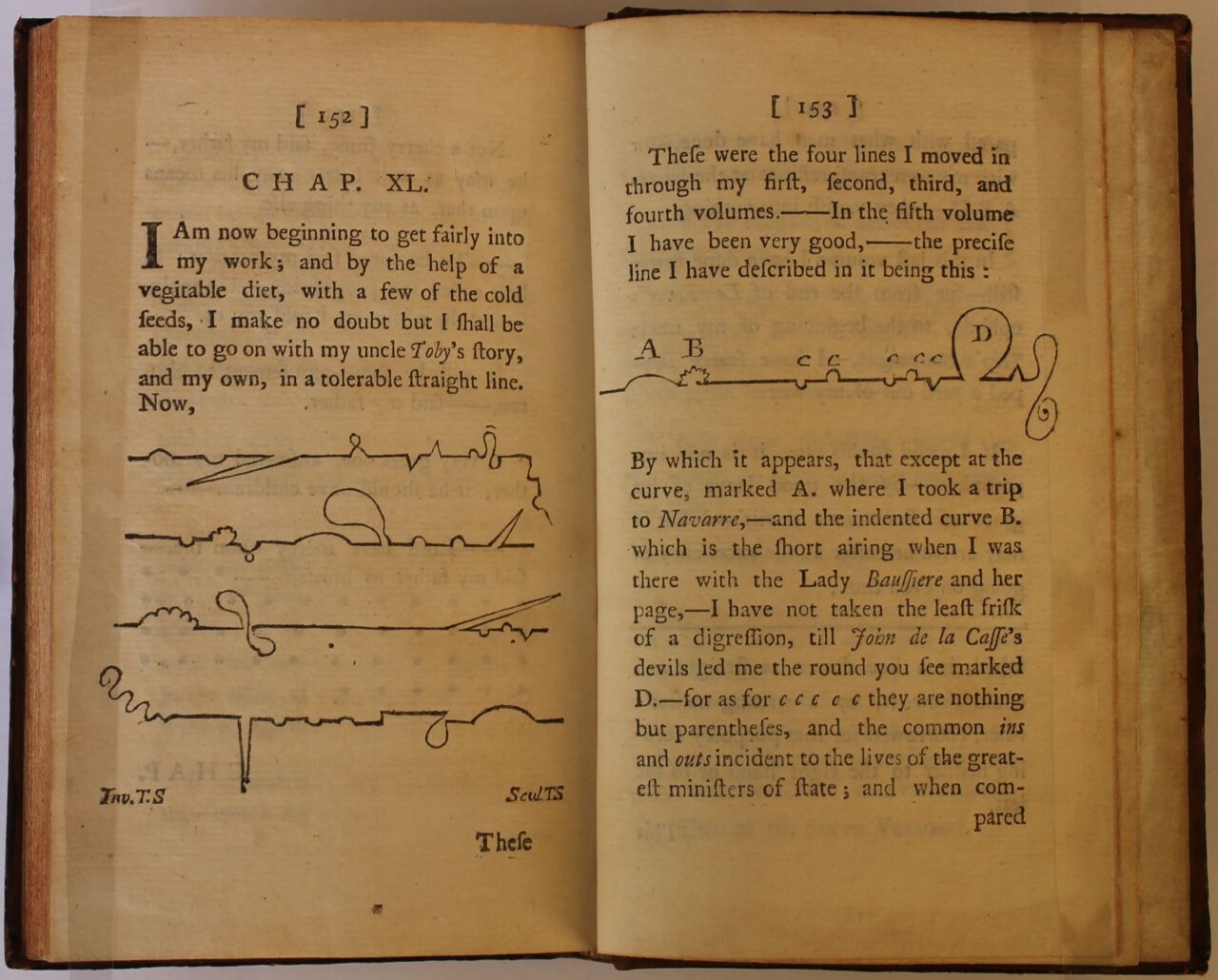

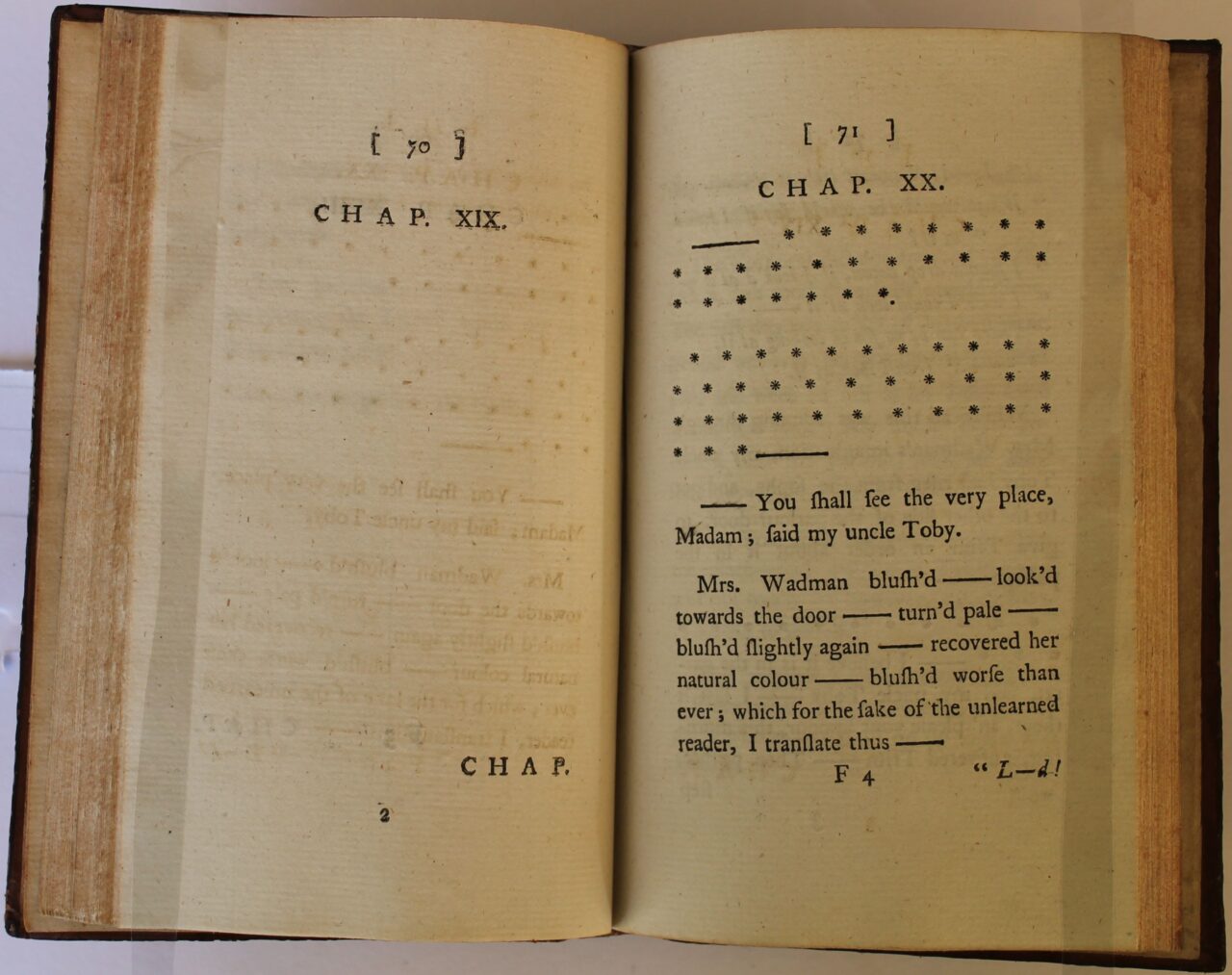

It was unlike anything that had been written before. Its narrative was disjointed. It had surprising visual insertions: a marbled page; a blank page; a black page; and various other visual interventions which challenged the printer as well as the reader. There was a missing chapter which caused a gap of ten pages in the pagination (the chapter was so good — claims the narrator — he had to remove it completely, lest the rest of the book suffer in comparison); paragraphs of asterisks for risqué passages; expressive squiggles, and so on.

(For more on these visual oddities see the British Library website.